The hidden influence of Persuasive Technology

We wake up to the glow of a smartphone screen, check a flurry of overnight notifications, and scroll through an endless feed of updates before even getting out of bed. It’s a routine shared by billions, and it underscores how pervasive artificial intelligence (AI) and persuasive technology have become in our daily lives. On average in 2023, people check their phones 144 times per day and spend over four hours daily on mobile devices – each micro-interaction carefully orchestrated by algorithms competing for our attention. Social media apps, news sites, games, and even productivity tools all leverage AI-driven “persuasive design” to nudge our behaviour in subtle ways. We are enticed to tap, scroll, like, and share, often without realising the psychological hooks at play. The popular documentary The Social Dilemma has illuminated how these persuasive technologies, especially on social media, are frequently deployed to profit from users’ attention at the cost of their wellbeing.

This ubiquity of AI-driven influence raises urgent questions: What are the consequences for our behaviour when every click is guided by an algorithmic prompt? How much of our “free will” is being quietly engineered by tech companies? And what does it mean for privacy when platforms gather intimate data to personalise this persuasion? In fact, research shows that with as few as 70 Facebook “likes,” algorithms can predict a person’s personality traits more accurately than that person’s close friends. The boundary between technology that serves us and technology that shapes us is blurring. Before we know it, we may find our choices – from the news we consume to the products we buy and the causes we support – are heavily steered by unseen AI systems fine tuned to influence our decisions. This article explores the hidden influence of persuasive technology and AI: how it works, the behavioural principles behind it, real world examples of its power, and the profound implications for our autonomy and privacy.

BJ Fogg’s behaviour model: the psychology behind persuasive design

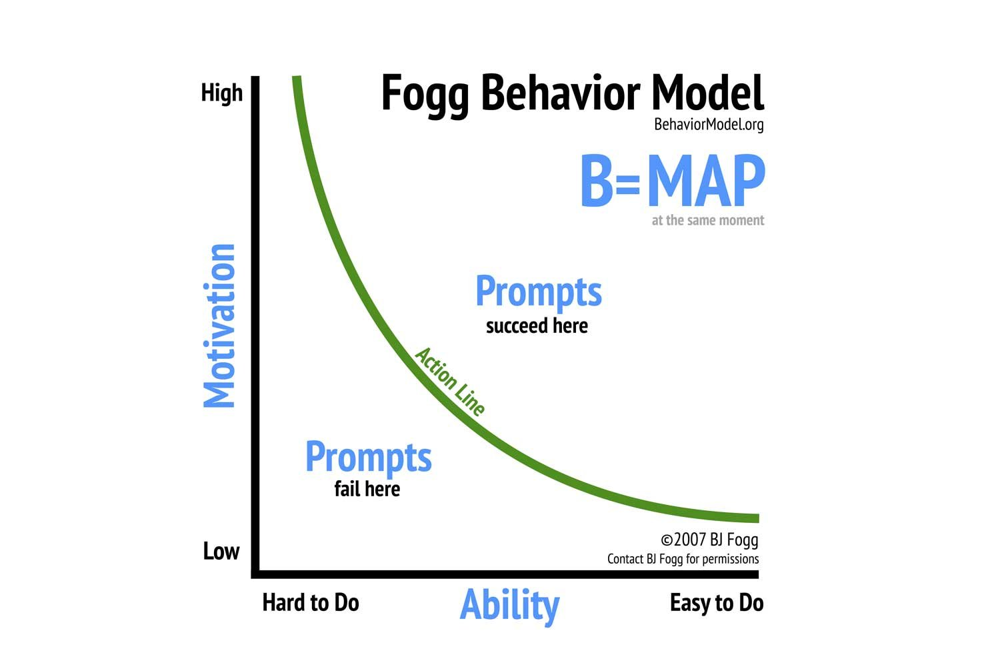

The Fogg Behaviour Model illustrates that a target behaviour occurs when three elements converge at the same moment: Motivation, Ability, and a Prompt. In other words, as Dr. BJ Fogg – a Stanford researcher who coined the term “captology” (Computers As Persuasive Technologies) in the 1990s – explains, “Behaviour happens when motivation, ability, and a prompt come together at the same time”. If a behaviour isn’t happening, at least one of these elements is missing. Fogg’s model (often summarised as B = MAP) has become a cornerstone for designing technology that influences user actions. It gives tech designers a formula for persuasion: to get a user to do something (B), you can increase their motivation, make the action easier (enhance their ability to do it), and/or deliver a timely prompt to trigger the behaviour.

In practice, these principles underpin much of modern persuasive design. Platforms boost our motivation by tapping into things we care about – for example, offering social approval, entertainment, or rewards. They simultaneously streamline the ability to act: one-click purchases, swipe interfaces, and autoplay videos remove friction so that taking action requires minimal effort. Finally, they deploy prompts (also called triggers) at just the right moments: think of the push notification that draws you back into an app or the subtle red badge that urges you to check an unread message. All three factors work in concert. A classic illustration is the Facebook “Like” system: users are motivated by the social reward of receiving likes, the interface makes it extremely easy to react or post (high ability), and prompts like notifications or the design of the feed cue users to keep engaging. As Fogg noted, when designers understand these levers, they can “create products that change behaviour” – for better or worse – by engineering motivation, ability, and prompts into the user experience. His Behaviour Model has been widely adopted, with many innovators and tech companies explicitly or implicitly using it to craft habit forming products.

BJ Fogg’s insights essentially gave Silicon Valley a recipe for capturing user behaviour. Importantly, Fogg himself emphasised ethical persuasion and “behaviour design for good,” but the industry hasn’t always heeded that caution. As we’ll see, the Fogg Model’s DNA is present in everything from social media apps to video games – fueling design techniques that hook users and subtly shape their daily routines.

Persuasive technology in social media, games, and apps

Persuasive design techniques have been woven deeply into the fabric of social media platforms, mobile games, and AI-powered apps. If you’ve ever found yourself compulsively refreshing your Instagram feed or unable to put down a game, you’ve experienced these techniques firsthand. They often leverage well known psychological mechanisms – variable rewards, feedback loops, and social validation – to keep us engaged.

Variable rewards: many apps operate on the principle of unpredictable rewards, a tactic borrowed from behavioural psychology experiments with slot machines. For example, every time you pull-to-refresh a social feed or check for notifications, you’re not guaranteed a “reward” (like a new like or message) – and it’s this uncertainty that makes it addictive. Platforms like Instagram even vary the timing and delivery of likes and comments on your posts to create a casino-like anticipation and dopamine rushr. This mimics B.F. Skinner’s classic finding that intermittent reinforcement (rewards at random or variable intervals) most strongly reinforces behaviour. As one analysis put it, “Mimicking the uncertainty of slot machines, platforms like Instagram vary likes and comments timing to heighten dopamine response”. Every scroll or refresh might surprise you with something gratifying – a funny meme, a friend’s photo, a piece of juicy news – which compels you to keep pulling the lever, so to speak. In video games, similarly, “loot boxes” and random prize drops exploit this principle: players keep playing (or paying) in hopes of a rare reward appearing by chance, a design so effective it has sparked comparisons to gambling and led some regulators to scrutinise it as an addictive mechanic.

Feedback loops and frictionless interaction: digital platforms create self-reinforcing feedback cycles that encourage us to continue using them. Consider the infinite scroll on social networks or the autoplay feature on streaming and video sites. YouTube’s autoplay will seamlessly queue up the next video, removing the tiny pause that might have allowed you to decide to do something else. This isn’t just a convenience – it’s an intentional design to “minimise decision friction and increase emotional stickiness”. By continuously feeding us content, the app keeps us in a loop where one action naturally leads to another. Mobile games use similar loops: completing a level gives you a burst of satisfaction and often immediately teases the next challenge, urging you to continue. These loops are often supercharged by AI-driven personalisation (which we’ll delve into shortly), so the content of the next item is highly likely to appeal to you, making the feedback loop even harder to break. Add to this a frictionless interface – no login required each time, easy swipes, simple taps – and the result is an experience where quitting requires more effort than continuing. As one observer noted, “Every refresh offers something new or unexpected… re-entry is effortless – no logout, no reset, just more feed.” This design keeps users continuously engaged without conscious decision points to interrupt the flow.

Social validation and peer influence: humans are inherently social creatures wired to seek approval and avoid rejection, and tech designers have not overlooked that. Social media platforms are built around social validation feedback – likes, follower counts, comments, shares, retweets, and streaks all serve as metrics of social approval that our brains latch onto. Each notification of a “like” on our post or a new follower triggers a small release of dopamine – the brain’s reward chemical – reinforcing the behaviour that led to it. Psychologically, we become conditioned to crave this positive feedback. Even the expectation of social rewards can hook us: the act of posting something puts us in a state of anticipation (Will people respond? How many likes will I get?), which keeps us checking our phones repeatedly. “When we receive social validation, the reward centers in our brain light up, and even the expectation of a positive reward releases that feel-good chemical, keeping us coming back”.

Platforms ingeniously amplify this effect through features like social proof – for instance, Twitter highlights when multiple people you know follow an account, nudging you to do the same. Instagram displays view counts and “liked by [friend] and others,” leveraging our tendency to follow the crowd. Snapchat introduced “Snapstreaks,” which show how many days in a row you’ve traded messages with a friend; the longer the streak, the stronger the implicit social bond. Users (especially teens) feel pressure to continue these streaks daily, sometimes obsessively, because breaking the chain induces a sense of loss or guilt. This is by design: “Snapchat streaks encourage daily engagement — breaking them triggers emotional dissonance”. In games and fitness apps, leaderboards and achievement badges play a similar role, tapping into competition and the desire for peer recognition.

Crucially, none of these features happened by accident – they were deliberately crafted based on behavioural science to “shape behaviour, prolong engagement, and convert time into value” for the platform. The architects of Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, and countless other services have openly acknowledged borrowing from psychology. As Chamath Palihapitiya, former VP of User Growth at Facebook, famously lamented, “the short-term, dopamine-driven feedback loops that we have created are destroying how society works”, referring to how these social validation cycles hook users and impact real-world social interaction. The result is that social media and games are not just products we use; they use us, training our reflexes and habits in a cycle of reward and craving. From the “Like” button to the “Share” button, from push notifications to infinite scrolling feeds, persuasive technology techniques have been embedded to make these experiences as habit forming as possible. We are kept perpetually “wired in,” chasing the next hit of social or content reward often without realising how neatly our behaviour is being guided.

How AI optimises engagement: behavioural profiles, personalisation, and emotion triggers

If persuasive design provides the toolkit for influencing user behaviour, artificial intelligence is the master craftsman that wields those tools with ever increasing precision. Today’s platforms don’t just use static tricks; they deploy adaptive AI systems that learn from each user’s behaviour in real time, continually tweaking the experience to maximise engagement. This is where persuasive technology steps up to a new level – moving from one-size-fits-all design patterns to hyper personalised, behavioural profiling and emotion triggering techniques tuned by machine learning algorithms.

Behavioural profiling: every tap, pause, swipe, and click you make is tracked to build a detailed profile of your preferences, habits, and even mood. For instance, “when you pause on a video for more than three seconds, TikTok learns. When you react with a laughing emoji instead of a ‘like,’ Facebook classifies your emotional bias.” In the background, AI models crunch this behavioural data to infer what kind of content you respond to, what times of day you are most susceptible to prompts, and which social signals affect you most. Over time, the system develops a profile of you – perhaps noting that you tend to watch political videos to the end, or you often replay a certain type of music clip, or you quickly scroll past posts about a particular topic. Modern platforms have thousands of data points on each user, and these are used to predict and shape future behaviour. It’s been said that social media knows us so well that algorithms can guess our personality or mood better than our friends can. Indeed, Facebook’s AI can infer when a user is feeling depressed or anxious based on posting patterns and engagement, and Uber’s algorithms can reportedly tell if a customer ordering a ride might be intoxicated, just from how they tap and hold their phone. This “de facto profiling” – drawing inferences about us from big data – doesn’t even rely on traditional personal info like name or age. The AI cares less about who you are than what characteristics and behaviours you exhibit. Those characteristics are gold for guiding persuasive strategies.

Personalised content feeds: using these behavioural profiles, AI systems curate the content you see to maximise your engagement. This is why your Facebook or Twitter News Feed, your TikTok “For You” page, and your YouTube recommendations are uniquely tailored to you. The algorithms test and learn what keeps you watching, clicking, or commenting, and then give you more of that. If you linger on cooking videos and skip sports clips, you’ll see more recipes and fewer football highlights. If political rants outrage you enough to make you comment or share, the algorithm takes note and serves up more of the same to elicit that response. TikTok’s famously addictive feed is a prime example: its AI rapidly figures out your niche interests (whether it’s Korean skincare routines or woodworking hacks) and then zeroes in on them with laser focus, eliminating any need for you to search or even think about what to watch next. The next video that appears feels uncannily relevant – often it is exactly what you didn’t know you wanted to see – making it “irresistible” to keep scrolling. One observer noted that TikTok’s algorithm “delivers hyper-relevant content, making ‘the next video’ feel irresistible”. This personalised feed creates a feedback loop: the more you engage, the more the AI learns what you like, which leads to even more engaging content, and so on. YouTube and Netflix similarly use recommendation engines to auto-play or suggest content tailored to your profile, aiming to maximise watch time. Over 70% of the videos people watch on YouTube are reportedly driven by algorithmic recommendations – a testament to how effectively personalised AI content can steer user behaviour en masse.

Emotion triggering and “Outrage” algorithms: beyond showing us what we like, AI has learned that how content makes us feel is a powerful lever for engagement. Studies and internal leaks have revealed that social media algorithms often prioritise content that evokes strong emotional reactions – especially anger and outrage – because that content keeps people glued to the platform and encourages them to interact (via comments, shares, etc.). “Algorithms consistently select content that evokes anger and outrage from users to maximise engagement,” as one report succinctly put it. This is why your feed might seem filled with polarising posts or sensational headlines: the AI isn’t trying to make you angry per se, but it has learned that when you’re angry or provoked, you’re more likely to engage deeply (debate, share, retweet with a comment). Unfortunately, those extreme emotions can spur extreme actions in the real world, contributing to societal polarisation. Facebook’s own internal research (brought to light by whistleblowers) noted that its algorithms, in certain periods, gave extra weight to reactions like the “Angry” emoji – treating them as five times more valuable than a “Like” – effectively boosting posts that infuriated people. In practice, this meant divisive or emotionally charged content spread further and faster. As one analysis of Facebook concluded, the platform “doesn’t produce divisive content – but it prioritises it”, since that content hits the engagement jackpot.

Beyond outrage, AI also taps into positive emotional triggers: content that makes us feel hopeful, amused, or validated can also keep us engaged. For example, the algorithms notice if wholesome, uplifting stories keep certain users around longer and will feed those to them. Similarly, if a fitness app’s AI finds that sending a motivational quote in the morning gets you to open the app and log a workout, it will do so when you’re most receptive. In all cases, the AI is continually experimenting (A/B testing) and refining its tactics: showing different content, observing reactions, and learning which approach best achieves the goal (usually measured in time spent, clicks, or other engagement metrics). As a result, the persuasive strategies you face are dynamic and ever more finely tuned to your individual psyche. One industry insider described this as social platforms “running continuous A/B tests on user behaviour to refine their nudges” – essentially letting the AI figure out how to nudge each person most effectively. The longer we use these platforms, the more data the AI has and the better it becomes at pushing our buttons.

To make the prompts themselves more effective, AI is also used to time them and target them. Have you noticed some apps seem to send alerts at exactly the moment you’re likely to give in and check? It’s not a coincidence – some services use machine learning to analyse your usage patterns and find the “optimal time” to send a push notification, i.e. when you’re most likely to respond. For example, an AI might learn that you usually have a free moment around 7:30 pm, after dinner, and choose that time to ping you with a tempting update. By doing so, it avoids alerting you when you’re busy (and might ignore it) and instead catches you at a vulnerable moment of boredom. These sophisticated tactics show how AI has turbocharged persuasive technology: it’s not just the static design of the app, but a responsive, learning system that adapts to each user to drive engagement. While this makes our apps and feeds eerily “addictive,” it also edges into problematic territory – leading to consequences for privacy and autonomy that we must reckon with.

Consequences: erosion of privacy, loss of autonomy, and behavioural manipulation

The rise of AI-driven persuasive technology comes with serious consequences. As platforms harvest intimate data and deploy ever more effective techniques to influence us, we face an erosion of privacy, a potential loss of personal autonomy, and new forms of manipulation of our thoughts and behaviours. What does it mean for society when our choices are being orchestrated by algorithms behind the scenes?

Erosion of Privacy: persuasive AI thrives on data – the more it knows about you, the more convincingly it can tailor its influence. This has led to an unprecedented explosion in the collection of personal information. Social media platforms track far more than what you explicitly post. They monitor location, device sensors, browsing history via trackers, contacts, and inferences drawn from all these. As a result, the platforms often know more about you than your closest friends and family do. One Washington Post investigation noted that Facebook’s algorithms could predict users’ personality traits or mood swings with startling accuracy, sometimes better than a spouse could The Cambridge Analytica scandal in 2018 starkly illustrated how such data can be misused: a political consulting firm obtained detailed Facebook data on up to 87 million users without their full knowledge, building psychographic profiles to target voters with tailored political ads. This wasn’t just a breach of privacy – it was a demonstration of how personal data could be weaponised to sway people’s opinions and behaviour. Indeed, subsequent research confirmed that this kind of “psychological targeting” is effective as a tool of digital persuasion.

What makes the privacy erosion particularly insidious is that it often happens invisibly. Users might consent to vague data sharing policies without realising the extent of inferences drawn about them. Modern AI doesn’t even need your name or explicit identifiers; by aggregating behaviour, it develops an implicit understanding of you. As one legal scholar pointed out, traditional data privacy laws struggle here because they focus on protecting “personally identifiable information,” whereas now it’s the profiles and predictions (which may not look like personal data on the surface) that drive persuasion. Your identity might be masked, but the platform still knows “a user with characteristics X, Y, Z” is susceptible to a certain nudge. In this sense, privacy as we used to define it – controlling who knows what about you – is under siege. Even when platforms claim to anonymise data, the behavioural patterns themselves become a proxy for your identity. The consequence is a world of diminished privacy, where companies can exploit intimate knowledge (moods, vulnerabilities, interests) to influence you, and where individuals often have little insight or control over what data is collected and how it’s used. We trade privacy for convenience and connection, perhaps not realising that the loss of privacy means a loss of power over our own decisions.

Loss of autonomy and free will: As persuasive technology gets more sophisticated, there is a genuine concern that our autonomy – our ability to make free, conscious choices – is being undermined. When algorithms expertly steer our attention and shape our preferences, our decisions may not be entirely our own. Consider how autoplay and endless feeds remove the “friction” of choice: often we consume content simply because it was served up, not because we actively sought it out. Over time, we can become passive participants, letting the algorithmic suggestions guide what we do next. Moreover, persuasive design exploits cognitive biases and subconscious triggers that we might not be aware of, meaning we are being influenced below the level of active decision-making. This raises ethical red flags: manipulation is most effective when the subject doesn’t realise it’s happening. If you think you’re just browsing videos, but in reality an AI has cultivated your lineup to push you toward a certain belief or to keep you from closing the app, your agency has been subtly co-opted.

Former Google ethicist Tristan Harris has warned that these platforms “are programming people” in a race for attention, effectively designing users rather than products. Shoshana Zuboff, author of The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, cautions that if behaviour-influencing by platforms continues unchecked, we risk a future where “autonomy is irrelevant… psychological self-determination is a cruel illusion”. That is a chilling statement – it suggests a world where our choices (what to buy, how to vote, whom to love, what to believe) could be so heavily shaped by AI nudges that the very concept of individual free will loses meaning. We’re not there yet, but signs of reduced autonomy are visible. Tech addiction is one example: many people feel compelled to check their phone first thing in the morning or repeatedly throughout the day, even when they consciously don’t want to. In one survey, over half of Americans said they feel addicted to their phones, and a large majority become anxious if separated from their devices. That compulsive behaviour isn’t just a personal failing – it’s the outcome of deliberate design. As users, our role has shifted from being customers to being subjects in vast experiments in persuasion.

Another aspect of autonomy is the ability to pay attention or not. Persuasive tech often exploits involuntary attention – notifications with flashing icons, vibration alerts, pop-ups – grabbing our focus before we can resist. This constant barrage can erode our capacity for sustained, autonomous attention (some studies link heavy social media use to decreases in attention span). When our attention is continuously being captured and steered externally, we lose the freedom to direct it as we choose. In a very real way, persuasive technology can commandeer the steering wheel of our mind. Ethically, this troubles the principle of respect for persons: technologies are treating people as means to an end (more engagement, more profit) rather than respecting their right to self-direct. We reach a point where, as users, we must exert significant willpower and conscious effort to counteract the pulls engineered into our devices – and not everyone can or wants to constantly fight those battles.

Manipulation of behaviour and beliefs: perhaps the most alarming consequence is how AI persuasion can manipulate human behaviour on a broad scale. It’s not just about one more video or one more purchase; it’s about shaping opinions, emotions, and actions at population scale. We’ve seen hints of this in various domains:

- Politics and misinformation: social media algorithms that prioritise engagement have inadvertently promoted misinformation and extreme content, because false or emotionally charged posts often garner high interaction. This has been linked to real-world effects such as political polarisation and even violence. Examples range from the role of Facebook in spreading inflammatory content during the Rohingya crisis in Myanmar, to the way online conspiracies gained traction and contributed to events like the January 6 Capitol riot in the U.S.. In these cases, persuasive algorithms amplified certain narratives and worldviews, effectively nudging segments of the population toward more extreme beliefs or confirming their biases (the “filter bubble” effect). Democracy is strained when voters are not operating on a shared set of facts but are instead each fed a tailored diet of news that might be skewed or manipulated. Cambridge Analytica’s micro-targeted political ads, mentioned earlier, were essentially an attempt to manipulate voter behaviour by leveraging personal psychological triggers. While it’s hard to measure exactly how much minds were changed, the very possibility of such fine-grained influence – persuading people at a subconscious level based on personality profiling – is a societal concern.

- Consumer behaviour and spending: persuasive tech also drives consumption patterns. E-commerce sites use AI recommendations (“Customers who viewed this also viewed…”) and limited-time offers to spur impulse purchases. Apps might manipulate pricing presentation or use dark patterns (like making the “subscribe” button bright and easy but the “cancel” process arduous) to influence economic behaviour. One analysis identified that Amazon leverages dozens of persuasive psychological tricks (like scarcity cues: “only 2 left in stock!”) to influence buying decisions. The result is consumers who can be led to purchase things they might not have otherwise, raising questions about consumer autonomy and exploitation. In the gaming industry, “freemium” games persuade players to spend on in-app purchases by first hooking them on the gameplay and then strategically increasing difficulty or offering shiny rewards behind a paywall. These are carefully orchestrated funnels that convert attention into revenue.

- Mental and physical health: our behaviours around health can also be manipulated – sometimes for good (fitness apps nudging you to exercise, or mental health apps encouraging meditation) but also potentially for profit (devices that send constant health alerts that might induce anxiety, prompting you to engage with a platform or buy health products). There’s concern that as health-related tech gets more persuasive (and integrated with AI predictions), it might lead people to excessive self-monitoring or unnecessary interventions, essentially persuading users that they have problems that need solving (often via a product or service).

What makes AI-driven manipulation particularly challenging is its opacity. The algorithms are complex and proprietary; users generally can’t see the logic behind their news feed or why a certain ad appears. That lack of transparency means manipulation can go undetected. You might not realise a surge of outrage you feel on a topic is partly stoked by an algorithm’s content choices tuned to push your emotional buttons. You might not realise that the reason you can’t stop scrolling a particular app is that the AI has silently learned how to press your unique triggers. We risk entering an age of “automatic persuasion,” where machine intelligence continuously tests and finds optimal ways to influence each of us, individually and collectively. The cumulative effect on society can be profound: privacy diluted, public opinion polarised, individuals more anxious and less autonomous. As one scholar argued, big tech’s pervasive use of behavioural-influencing science – especially when it’s covert and one-sided – may cross the line into the manipulative, undermining the dignity and autonomy of userslens.

Recognising these consequences is the first step. The next crucial step is addressing them – which requires both ethical design changes by companies and proactive policy and regulation by governments.

Real world examples and case studies of Persuasive AI

Persuasive technology and AI are not abstract concepts; they are deployed by virtually every major tech platform and many smaller ones. Here are a few prominent examples and case studies that highlight how companies use persuasive AI to shape user behaviour:

- Facebook and Instagram: Facebook’s News Feed algorithm is a classic case of persuasive AI in action. It uses thousands of signals (your past clicks, dwell time on posts, reactions, etc.) to personalise your feed and keep you scrolling. In 2018, Facebook tweaked this algorithm to prioritise content that sparked “meaningful interactions,” which in practice often meant posts that provoked debate or strong reactions. Internal documents later revealed that the algorithm had been weighting comments and reactions (like the “Angry” emoji) heavily, which unintentionally boosted provocative content that made users angry or excited. This led to increased engagement, but at the cost of amplifying divisive material – a pattern so concerning that some Facebook insiders described the system as an “outrage algorithm.” On Instagram, persuasive design manifests through the infinite scroll of the feed and the use of variable rewards. Instagram’s designers implemented the pull-to-refresh mechanism (similar to a slot machine lever) and reportedly adjusted the timing of showing likes on your posts to be not instant but delayed or batched, creating moments of delight when a bunch of new likes appear at once. The platform also leverages social validation through features like showing which friends liked a post and the overall like counts, tapping into users’ need for social approval. Together, Facebook and Instagram (both under Meta) have perfected a business model of keeping users “engaged” – meaning glued to the screen – through AI-curated content and notifications that draw you back whenever your attention wanders.

- TikTok and YouTube: TikTok has become almost synonymous with addictive viewing, thanks to its formidable AI content recommendation engine. When a new user joins TikTok, the app quickly starts showing a variety of videos and observing how you react – which ones you watch fully, which you swipe past, where you pause. Within a surprisingly short time (often just an hour or two of use), TikTok’s algorithm converges on your tastes with uncanny accuracy. Love cooking? Dog videos? Dark humor? It figures it out and then serves an endless stream of exactly that. This personalised feed is so compelling that TikTok’s average watch times far outpace other social apps. Users often report losing track of time, spending hours on the app without intending to. The immersive, full-screen design ensures each video captures complete attention, and the never-ending scroll means there’s always another hit of entertainment waiting. YouTube, similarly, uses AI to recommend videos – an innocuous-sounding feature with significant impact. Autoplay ensures that after one video, another (algorithmically chosen) one starts. Over 70% of the view time on YouTube is driven by these recommendations. This has been beneficial in keeping viewers on the platform (great for ad revenue) and introducing them to new content, but it’s also been criticised for sometimes leading viewers down “rabbit holes.” For instance, a user watching an innocuous political video might be recommended slightly more partisan or sensational content next, and gradually the recommendations grow more extreme to keep engagement high. While studies differ on how much YouTube’s algorithm radicalises people, the company has had to adjust its AI in recent years to demote conspiratorial content and up-rank authoritative sources, acknowledging the persuasive power it wields over public opinion.

- Snapchat and social gaming: Snapchat pioneered several persuasive features targeted at its mostly younger user base. The Snapstreak feature – counting consecutive days of messaging with someone – created a game-like social obligation. Teens would often feel pressure not to break streaks, even giving friends access to their accounts when they went on vacation just to send streak-maintaining snaps. This drove daily active use because it turned communication into a game of consistency. Snapchat’s design also uses ephemeral content (stories that disappear in 24 hours) to generate a sense of FOMO (fear of missing out) – if you don’t check in frequently, you might miss what your friends posted. This plays on loss aversion and keeps users coming back regularly. In the realm of gaming, especially mobile games, persuasive technology is omnipresent. Games like Candy Crush or Clash of Clans hook users with easy initial rewards and levels (to build confidence and habit), then progressively increase difficulty or introduce wait times that nudge players toward making purchases for boosters or more play time. These games use bright celebratory visuals and sounds as positive reinforcement when you succeed, and they often present challenges just tantalisingly achievable enough that you keep trying (“Just one more try!” syndrome). Many mobile games implement compulsion loops – a cycle of completing tasks to get rewards that open up new tasks – which can strongly engross players. The introduction of random reward mechanics like loot boxes (virtual crates with random items/prizes) in games exemplifies persuasive design for profit: players are drawn into spending real money for a chance at a rare item, engaging the same psychology as gambling. It’s such a direct use of variable rewards that some countries have debated or enacted regulations on loot boxes, concerned about their impact on young players’ behaviour.

- Amazon and e-commerce platforms: online shopping platforms have quietly become masters of subtle persuasion, using AI and design to influence buying behaviour. Amazon, for one, employs AI recommendation engines on nearly every page: “Customers who bought this also bought…” or “Inspired by your browsing history…” These personalise the storefront to each user, often uncovering products the user wasn’t actively looking for but is likely interested in (thereby increasing impulse buys). The site also uses techniques like urgency and scarcity messages (“Only 3 left in stock – order soon!”) to persuade customers to check out quickly rather than ponder a purchase. Countdown timers for deals and one-click purchasing are other examples of reducing the ability barrier – making it so easy and so urgent to buy that you are nudged to proceed. E-commerce apps send personalised push notifications, say when an item you browsed goes on sale, pulling you back in with a tailored prompt. Even after a purchase, AI follows up: you’ll see prompts to leave a review (leveraging consistency/reciprocity principles: you got a product, now give back feedback) or to buy complementary products. While these tactics are not as publicly scrutinised as social media algorithms, they are highly effective in shaping consumer behaviour and have turned platforms like Amazon into habit-forming shopping destinations for millions.

- Cambridge Analytica (political persuasion case): no discussion of persuasive technology would be complete without this notorious case, which serves as a wake-up call about how AI and data can be used to influence behaviour on a societal level. Cambridge Analytica was a UK-based firm that, in the mid-2010s, acquired extensive Facebook user data through a third-party app and built “psychographic” profiles of voters. The idea was to combine personality psychology with big data: categorise people by traits (e.g., neurotic vs. stable, introverted vs. extroverted) inferred from their online activity, then craft tailored political messages more likely to resonate with each type. For example, a highly neurotic, security-focused person might see an election ad emphasising law-and-order issues, whereas an extroverted, socially motivated person might see a message emphasising community and patriotism. Cambridge Analytica reportedly used such micro-targeted advertising in the 2016 US presidential campaign and other elections. As a case study, it highlighted both the erosion of privacy (tens of millions of users had their data scooped up without informed consent) and the potency of AI-driven manipulation (ads delivered to susceptible individuals at the right time, in the right emotional tone, to influence voting behaviour). While it’s debated how decisive these efforts were in outcomes, they demonstrated the principle that, given enough data about people, algorithms can segment and sway an audience with far more precision than traditional mass media campaigns. It was a learning moment that persuasive technology isn’t just about making us click ads – it can potentially alter the course of democracies by nudging individual voter behaviour at scale.

These examples barely scratch the surface. We could also discuss how Netflix’s autoplay and recommendation algorithms created the binge-watching phenomenon, or how Duolingo (a language learning app) uses streaks and gamified rewards to persuade users to practice daily, or how Google Maps nudges drivers into certain routes (which has urban-scale effects on traffic). In each case, the themes echo what we’ve outlined: harnessing data about users, employing psychological triggers (reward, fear of loss, social proof), and using AI to constantly refine the approach. The companies deploying these methods have seen enormous success in terms of user engagement and growth, which is exactly why these techniques have proliferated across industries. Yet, as we’ve noted, the success comes with side effects – some unintended, some perhaps knowingly risked – on users’ wellbeing and autonomy. Recognising these patterns in real-world systems arms us, as users and citizens, with awareness: we can start to see when we’re being played by design, and that awareness is a prerequisite for demanding change.

Ethical implications and toward ethical AI, responsibilities of companies and policymakers

The power of persuasive AI to shape human behaviour puts a significant ethical responsibility on the shoulders of those who design and deploy these technologies. There is growing recognition that we need a new paradigm – one of ethical AI and humane technology design – to ensure that these systems respect users’ autonomy, privacy, and wellbeing. Both corporate leaders and governments have crucial roles to play in steering the future of persuasive technology toward positive outcomes rather than dystopian ones.

Ethical Design Principles: One foundational idea proposed by early technology ethicists is a kind of “Golden Rule” for persuasive tech: Designers should never seek to persuade users to do something that the designers themselves would not want to be persuaded to do. In other words, persuasion should not be about exploiting users for profit or influence in ways that the creators would find manipulative or harmful if they were in the user’s shoes. This principle forces empathy and could rule out the most egregious dark patterns and manipulative tactics. For example, if a social media executive knows that endless scrolling and outrage-filled feeds make them anxious or angry in their own life, they should hesitate to impose that design on millions of others.

Another key principle is transparency. Users should have clarity about when they are being influenced or guided by an AI. This might involve platforms providing more insight into “why am I seeing this post/ad?” or clearly labeling when content is boosted due to your profile. Transparency also means being open about what data is collected and how it’s used to personalise experiences. Currently, much of this happens in a black box. Requiring intelligible explanations of algorithmic choices (an area of AI ethics research known as explainable AI) can empower users to make informed choices. For instance, if YouTube were to tell a user “you watched video X, so we’re suggesting Y,” the user might become aware of the pattern and decide, “Actually, I’ve had enough of that topic.” Some social platforms have added features to let users adjust their content preferences or switch off personalisation (Twitter allowing a chronological feed as an alternative to the algorithmic feed, for example) – moves in the direction of giving control back to the user.

User agency and control: ethical persuasive technology should enhance user agency, not diminish it. This means building in opt-in mechanisms and respecting consent. Instead of defaulting users into addictive feedback loops, systems could invite users to set their own goals and boundaries. Imagine a social app that, on sign-up, asks what you value (e.g. “help me stay in touch with friends – but not at the expense of work/family”) and then aligns its algorithms accordingly, even if that means reducing engagement metrics. While this might sound idealistic in today’s attention economy, it speaks to designing for user wellbeing rather than maximum usage. Features like screen time reminders, quiet modes, or the ability to disable infinite scroll or autoplay are small steps some apps have taken to let users rein in usage. Apple and Google both added system-level digital wellbeing tools (like iOS’s Screen Time) to help people monitor and limit their app usage – an implicit nod that tech can be too persuasive and that users need countermeasures.

Companies could also consider age-appropriate design as an ethical imperative, given that children and teenagers are particularly vulnerable to persuasive tricks. The UK’s Age Appropriate Design Code (2021) has pushed platforms in this direction by requiring higher default privacy and wellbeing settings for minors. In response, companies like TikTok made changes such as disabling push notifications at night for teen users (no notifications after 9pm for users 13-15, for example), so as not to disrupt sleep or study. This is a concrete example of ethical design: recognising that what maximises engagement (sending pings at all hours) might harm young users, and therefore choosing to dial it back. Ethical AI design would generalise this kind of thinking – prioritising human needs (like mental health, sleep, focus) over the maximal extraction of attention.

Corporate responsibility: Tech companies need to build ethical considerations into their business decisions and development processes. This can include establishing internal ethics teams or review boards to vet new features for potential harms (though these need genuine influence, not just a ceremonial role). Some organisations have proposed ethical frameworks for AI – for instance, Google published AI Principles in 2018 pledging to avoid applications that violate human rights or yield unfair outcomes. While persuasive tech wasn’t explicitly singled out, the principle of respecting user autonomy can be derived from such frameworks. Social media companies could, for instance, decide not to amplify content that, while great for engagement, is shown to be harmful to society or individuals (Facebook’s leadership faced this choice regarding outrage content).

Companies can also invest in research and development of “humane tech” – technology designed to help users, in Tristan Harris’s words, “align with humanity’s best interests.” This might mean innovations that measure success by user satisfaction or long-term wellbeing rather than minutes spent. It’s a challenge because it might conflict with short-term profits, but some companies are beginning to realise that user trust and sustainability of engagement matter more than just quantity of engagement. If users burn out or grow cynical about a platform that manipulates them, that’s bad for business long-term. Thus, enlightened self-interest could drive companies to moderate their persuasive tactics. Netflix, as an example, introduced an “Are you still watching?” prompt that appears after a few episodes of continuous binge-watching – a minor friction that actually asks the user to confirm they want to keep going. While likely intended to save bandwidth and not annoy users who fell asleep, it also has the side-effect of injecting a tiny bit of mindfulness into an otherwise automatic binge session.

Government and policy interventions: Relying on companies to police themselves, however, may not be sufficient. Regulatory oversight and public policy are increasingly being called upon to address the societal impacts of persuasive technology. Data privacy laws like the EU’s GDPR and California’s CCPA give users rights over their personal data (access, deletion, opting out of sale), which indirectly limits how freely companies can collect and use data for targeting and persuasion. However, as discussed, these laws have limitations in addressing inferred data and algorithmic influence. We may need new regulations specifically targeting algorithmic transparency and accountability. For example, the EU’s draft Digital Services Act (DSA) and Digital Markets Act include provisions requiring large platforms to explain their recommendation systems and allow users to opt-out of profiling-based feeds. This kind of law could force, say, a social network to provide a mode that isn’t constantly optimising for engagement (perhaps a simple chronological feed or one sorted by content type). Additionally, regulators are considering whether certain AI-driven practices should be deemed unfair or deceptive. In the realm of consumer protection, one could imagine rules against designing interfaces that exploit cognitive biases in extreme ways (some U.S. lawmakers have even proposed banning infinite scroll and autoplay for users under a certain age, to curb addiction).

Another policy approach is algorithmic auditing: requiring platforms to allow external auditors or researchers to examine how their algorithms operate and whether they have biases or harmful effects. Independent audits could catch, for example, if a platform’s AI is disproportionately serving extreme content or if certain vulnerable groups (like people with addictive tendencies) are being specifically targeted with persuasive nudges (like gambling ads or other harmful content). If findings are negative, regulators could mandate changes or fines. This moves persuasive tech out of a purely self-regulated domain into one with public accountability.

Crucially, policymakers are also looking at the mental health impacts of social media and considering legislation. For example, some jurisdictions have discussed labeling requirements (similar to health warnings) for apps that pose addiction risks, or even legal liability if platforms knowingly design features that cause clinical addiction or harm to minors. While it’s tricky to legislate “persuasion,” framing it in terms of safety and health might be effective. Just as there are regulations on advertising (you can’t advertise cigarettes to kids, for instance), there could be rules on how far platforms can go in pushing psychological buttons, especially for minors. The comparison has been drawn between big tech and Big Tobacco, with persuasive tech being likened to nicotine that hooks users. In fact, a former Facebook investor once suggested platforms should come with warning labels about their potential to be addictive.

Toward ethical AI: on a higher level, building ethical AI that underpins these systems means incorporating values like fairness, respect for autonomy, and beneficence (doing good, or at least avoiding harm) into algorithm design. AI engineers could, for example, modify engagement-optimising algorithms to include parameters for diversity of content (to avoid extreme filter bubbles) or to deliberately promote wellbeing metrics (if such can be defined – a nascent area of research). Imagine if your feed algorithm not only tried to maximise your time on site, but also tried to maximise a metric of “user satisfaction” that accounts for whether you felt your time was well spent. This requires finding better metrics than raw engagement – a challenge the industry is slowly acknowledging. Some social apps have started surveying users about their experience (questions like “did this post make you feel inspired or upset?”) to gather data on qualitative impact, not just clicks. Such feedback can train AI to optimise for more than attention – perhaps for positive emotional impact or informative value.

Finally, ethical AI must also consider inclusivity and avoiding harm to vulnerable groups. If an AI notices a user might be in a fragile state (e.g., someone watching content about depression or self-harm), ethical programming would dictate the system not exploit that with persuasive tricks, but rather perhaps surface supportive content or even throttle back on potentially harmful engagement loops. There have been instances of algorithms unfortunately steering vulnerable individuals to harmful communities or content because it kept them engaged. A humane approach would flag and adjust those situations.

In sum, the path to ethical persuasive technology involves a cultural shift in tech – from growth-at-all-costs to responsibility – and smart governance that can set boundaries and incentives for healthier innovation. Tristan Harris’s Center for Humane Technology and other advocacy groups are pushing this narrative, urging both Silicon Valley and Washington (and other governments worldwide) to reckon with the social impact of these platforms.

A call to action for a human-centric tech future

Persuasive technology powered by AI has undeniably changed how we live, from the small habits of our morning routines to the broad currents of our society. We stand at a crossroads: continue on the current path, allowing invisible algorithms to increasingly commandeer human behaviour, or consciously redirect the trajectory toward technologies that empower rather than exploit. The hidden influence of AI on our behaviour and privacy can no longer remain in the shadows – it’s a phenomenon we must bring into public awareness and debate.

The future, if nothing changes, is a sobering one. We could find ourselves in a world where our attention is perpetually fractured, flitting from one algorithmically curated stimulus to the next, our capacity for independent thought and deep focus diminished. Privacy could become a quaint relic of the past, as persuasive systems intrude into even the most intimate corners of our lives to gather data and push our buttons. Our society could grow more polarised and manipulable, as each person lives in a personalised digital reality tuned to trigger them emotionally – a fertile ground for misinformation and social conflict. In the worst case, we risk what some have called “the automation of deception and manipulation,” a scenario where AI systems automatically figure out how to deceive us in the name of engagement or profit. That is not a future worthy of the extraordinary potential of technology.

But this future is not inevitable. The same ingenuity that built these persuasive systems can be harnessed to build ethical, transparent, and user-centered systems. As users, we can start by taking back some control – being mindful of how we spend time online, using tools to set boundaries, and demanding better from the products we use. Every individual act, like turning off non-essential notifications or choosing to support platforms that respect your time and privacy, is a vote for a different approach to tech. As the saying goes, if you’re not paying for the product, you are the product – so perhaps we must become willing to pay (with subscriptions or other models) for services that don’t treat us as targets for persuasion.

More importantly, as a society we must hold companies and policymakers accountable. We should encourage legislation that treats excessive psychological manipulation by apps with the seriousness with which we treat other public health and consumer protection issues. We should support organisations and leaders advocating for humane technology – those reimagining metrics of success in Silicon Valley to include user flourishing, not just user acquisition. We have historical parallels to draw on: just as environmental regulations and consumer safety laws eventually tempered the industrial boom, we need a framework to mitigate the “attention economy” boom and its toxic byproducts. Already we see momentum: whistleblowers are speaking out, governments are launching inquiries into social media’s impact, and tech insiders are coming forward to change the culture from within.

In crafting this article, the goal has been not to vilify technology, but to illuminate the often unseen mechanics of persuasion so that we can approach them with eyes wide open. AI and persuasive design are tools – incredibly powerful ones – and like any tools, they can be used for good or ill. We have seen how they can deteriorate privacy, autonomy, and trust. Yet they could also be used to build up positive habits (imagine AI that persuades people to save money, to learn new skills, to engage with their community offline) and to facilitate personal growth and knowledge. The difference lies in intent and ethics. By insisting on ethical guardrails and a human-centric ethos, we can reclaim technology as a force that serves our genuine needs and values.

The hidden influence of persuasive technology doesn’t have to remain hidden. Let’s drag it into the light, have the hard conversations, and shape a future where AI works with us rather than on us. Our behaviours and minds are our own – and it’s time to assert that, in the digital realm just as much as the physical. The call to action is clear: designers, regulators, and users alike must push for a tech ecosystem that honors human agency and privacy. If we succeed, AI will still shape our lives, but it will be as a helpful guide or thoughtful assistant – not as an invisible puppeteer pulling the strings of our behaviour. It’s a future where technology truly augments our humanity instead of exploiting our vulnerabilities. That is the promise we must demand, and the standard to which we must hold the next generation of persuasive technologies. Our collective digital wellbeing depends on it.

At BI Group, we are committed to leading the way in Responsible AI – creating AI solutions that empower, not exploit. Through our initiatives, we aim to ensure that AI works with humanity, rather than on us, fostering an environment where technology aligns with the best interests of people and the planet. We invite you to join us in creating a future where AI serves society ethically and responsibly.

Together, we can build technology that respects privacy, promotes autonomy, and empowers individuals to reclaim control over their digital lives. Let’s act now to ensure that AI remains a tool for good, not a force that shapes us without our consent.